Games: are they necessarily good for your child?

Ask a parent to let her child play computer games in place of watching an educational video to learn the same thing, and we will tend to see expressions of doubt, a little wonder and even disapproval. This is all very understandable, since games, especially the digital ones, do not have a great reputation over the years, having been associated with such terms as gaming addiction, fun and entertainment. A game to promote serious learning, with rigor? You must be joking.

There are games that distract, and there are games that teach. How can we tell them apart?

As early as 2009, experts have argued that:

games can engage players in learning that is specifically applicable to “schooling;” and there are means by which teachers can leverage the learning in such games without disrupting the worlds of either play or school.

As much as we wish to deny and exercise control over our children’s exposure to games, we can no longer deny that digital games are so much a part of our children’s lives, so ingrained in the ecosystem of the devices they interact with, almost at every waking moment. So the ability to discern and choose the right gaming product for our children is critical.

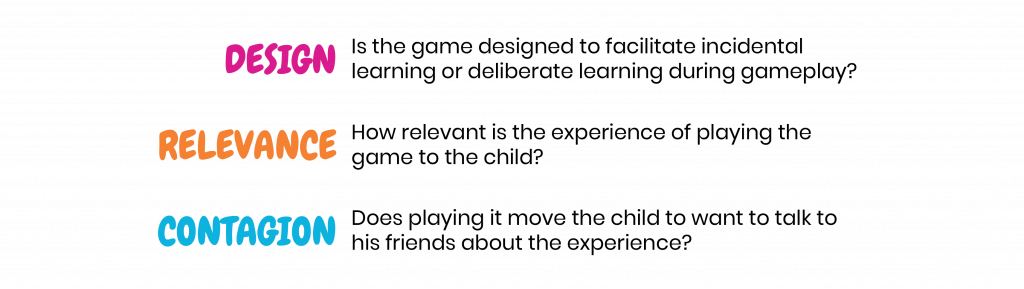

I would recommend that we look to the following criteria when discerning whether a game is good for your child. These criteria rank in order of decreasing importance:

Game Design is paramount

Game-based learning resources need to have learning at the front of their design. This means that any game that is designed for learning should feature activities that involve the cognitive or affective application of key concepts that a learner should be learning as part of the gameplay. This is what I call ‘deliberate learning in gaming’. It contrasts with ‘incidental learning’, where a learner begins to grasp some elements of a concept only after repeated trial-and-error attempts. Deliberate learning is a more productive way to learn and when it is core to a game design, the game becomes an efficacious and engaging instructional instrument. STEAMValley is one such example of a learning game that is designed with deliberate learning in mind. Nested within STEMWerkz (www.stemwerkz.org), it challenges the learner to make calculations and mathematical projections on cost-to-benefit analyses, apply design principles in town planning, while solving problems in science and technology within the town of STEAMValley. In playing this game, the learner becomes a problem identifier and a solver at the same time, while learning the basic concepts of science and seeing their applications in real-life situations.

Only meaningful experiences are relevant to the learner.

When an experience is meaningful, it becomes engaging. In the domain of STEM, meaningful experiences are often derived from an understanding of how nature responds to changes, and from the ability to solve a problem in the natural or artificial world. In the younger years, learners could derive meaning and joy from assembling something (think Lego bricks), winning something (think competitions), achieving something (think recognitions, especially the unique ones like baseball cards). These activities add to the self-actualization in the learner’s pool of needs, and help to build self-confidence and interest in these activities. In the digital world of STEM education, unique awards, badges and digital objects can be highly effective in making the total learning experience highly meaningful to the learner. For example, in STEMWerkz Quests, a learner achieves a unique digital badge with every successful completion of a learning packet. This badge takes on a physical form when it is mailed to the learner for her to pin it on her school bag to show her friends. This also inadvertently builds social currency as the learner is able to show and demonstrate what she now knows.

A contagious learning experience builds buzz in a positive upward spiral

What makes us want to talk about something to our friends? One part of the answer comes from what Jonah Berger calls ‘Social Currency’, which he defines as “about people talking about things to make themselves look good, rather than bad”. This isn’t a bad thing and should not be brushed off as an act of trying to show off. On the contrary, when oversighted with the right mindset, it can be a powerful force that drives people to better themselves and contribute to their micro-environment and community. From our experience, a learner develops social currency when he shows, shares and compares what he knows or has with his peers. Take STEAMValley Challenge for example — in this digital competition, the top 10 players each month are awarded a unique building that they can install in their towns. The ability to visit other players’ towns and explore their friends’ town designs also accord another dimension for sharing, making the learning experience more contagious.

So why is a learning experience that is contagious good for your children? This is because when people play or learn as a group, the sense of community attracts them to the learning experience, motivating them to participate, deriving joy in the process (also known as having fun). That’s why we see many successful online games often have features that encourage players to work together and build communities, which in turn increases player engagement, sometimes dangerously to the point of addiction.

Thus, while a contagious learning experience is one of the considerations for a game that is good for our children, it should be the least important of three considerations I have proposed earlier, but it is still an important one to look at, because ultimately, we want our children to be engaged in the learning process, in the right way, and for the right reasons.